I’m building a simple synth on a breadboard, where the frequency is defined as \(f=\frac{1}{RC}\), so by using different resistors with a row of buttons, different tones can be made. But what if you press two buttons simultaneously? You get 2 parallel resistors, giving:

\[R=\frac{R_1 \cdot R_2}{R_1 + R_2}\]I stumbled on this while playing with it, and the combined tones seem to be nice intervals sometimes. So I started to wonder if there was a connection.

In 12-tone equal temperament, the ratio of the frequency between two notes is \(\sqrt[12]{2}\), so we could just plug it in and see what comes out. Take a series of notes:

\[f_b(n)=f_a\cdot\left(\sqrt[12]{2}\right)^{n} \\ T_a=\frac{1}{f_a} \\ T_b(n)=\frac{1}{f_b(n)}=\left(\sqrt[12]{2}\right)^{-n} \\\]And a series of a combined frequencies:

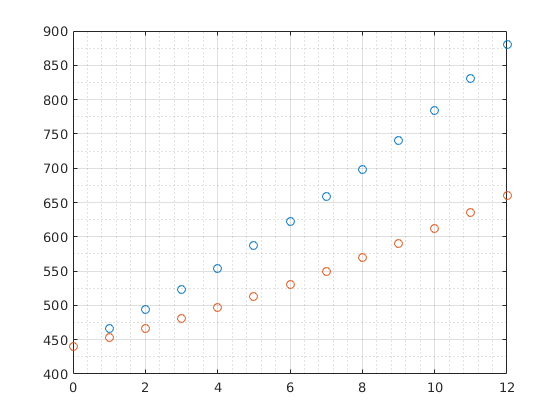

\[T_t(n)=\frac{T_a \cdot T_b(n)}{T_a + T_b(n)} \\ f_t=\frac{1}{T_t}=\frac{T_a + T_b(n)}{T_a \cdot T_b(n)}\\\]Plotting these in Matlab gives the following result

base = 220;

bp = 1/base;

tones = base.*(nthroot(2,12).^(0:12));

periods = 1./tones;

r = (bp.*periods)./(bp+periods);

duotones = 1./r;

plot(0:12, tones.*2, 'o', 0:12, duotones,'o');

grid on

grid minorAs can be seen, some combined tones are indeed quite close, but most not exactly. But then equal temperament does not have exact harmonics either. So we still do not know if we are generating actual harmonics, or just frequencies that happen to be close.

So what if instead of starting with \(\sqrt[12]{2}\), we start with integer multiples of the base frequency and fold then back into one octave. This gives:

\[\frac{1}{1}, \frac{2}{1}, \frac{3}{2}, \frac{4}{2}, \frac{5}{3}, \frac{6}{3}, \frac{7}{4}, \frac{8}{4}, \frac{9}{5} \ldots\]Plugging that into the parallel resistance equation, we can begin to search for exact harmonics giving exact harmonics.

harm = 1:31;

harm_cap = zeros();

for i = harm

j = i;

while j>2

j= j/2;

end

harm_cap(i) = j;

end

period = 1./harm_cap;

par = (1.*period)./(1+period);

freq = 1./par;

freq_cap = zeros();

for i = harm

j = freq(i);

while j>2

j= j/2;

end

freq_cap(i) = j;

end

[C,ia,ib] = intersect(harm_cap, freq_cap)| Combined Harmonic | Name | Button ratio | Name |

| 17 | Minor second | 9 | Major second |

| 9 | Major second | 5 | Major third |

| 19 | Minor third | 11 | Tritone |

| 5 | Major third | 3 | Fifth |

| 11 | Tritone | 7 | Minor seventh |

| 3 | Fifth | 2 | Octave |

| 2 | Octave | 1 | Prime |

And we can indeed verify that two resistors with a 2:1 ratio give a fifth (3:2):

\[f=\frac{1 + 2}{1 \cdot 2}=\frac{3}{2}\]Likewise a resistor ratio for a fifth gives a major third (5:3)

\[f=\frac{1 + \frac{3}{2}}{1 \cdot \frac{3}{2}}=\frac{5}{3}\]Math, music, physics. So beautiful.

Update:

As pointed out by Darius Bacon, this might not be a complete surprise, as there is a striking similarity between parallel resistance and the harmonic mean.

\[H = \frac{n}{\frac{1}{x_1} + \frac{1}{x_2} + \cdots + \frac{1}{x_n}} \\ R_\mathrm{total} = \frac{1}{\frac{1}{R_1} + \frac{1}{R_2} + \cdots + \frac{1}{R_n}}\\\]Wikipedia also has the following to say about the harmonic series:

\[\sum_{n=1}^\infty\,\frac{1}{n} \;\;=\;\; 1 \,+\, \frac{1}{2} \,+\, \frac{1}{3} \,+\, \frac{1}{4} \,+\, \frac{1}{5} \,+\, \cdots\]Its name derives from the concept of overtones, or harmonics in music: the wavelengths of the overtones of a vibrating string are 1/2, 1/3, 1/4, etc., of the string’s fundamental wavelength. Every term of the series after the first is the harmonic mean of the neighbouring terms; the phrase harmonic mean likewise derives from music.