I have previously talked about how I got pulled into building soccer robots at Roboteam Twente. During the summer holiday I spent a lot of time thinking about their code and about ways to improve it. During this time I wrote 3 different behavior tree implementations, and stumbled upon something that I’ve not seen in any of the literature on behavior trees. (Behavior trees are basically state machines on steroids)

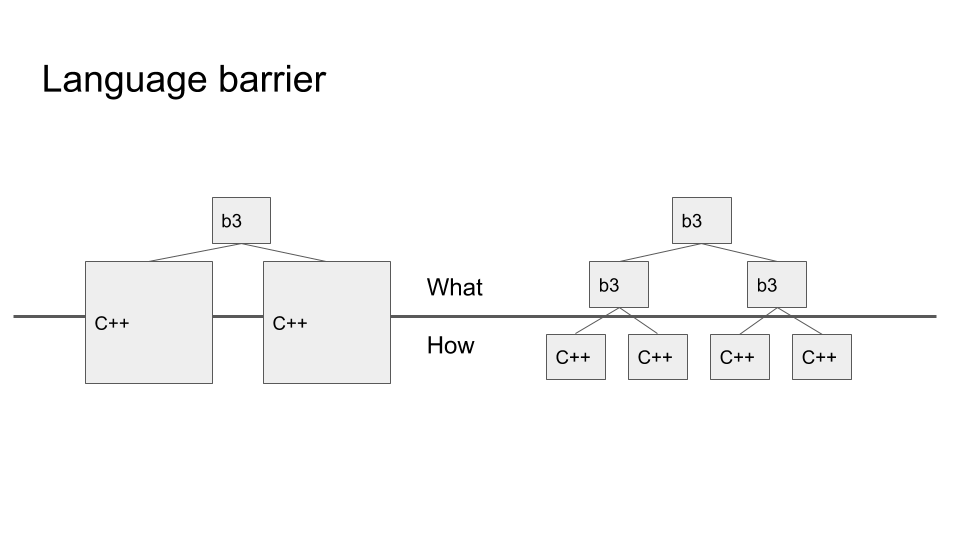

The main problem I was trying to solve is that over time, the leaf nodes that should contain the “how” in a tree of “what” had gotten increasingly large and complex, and it was desired to split those up in smaller tasks.

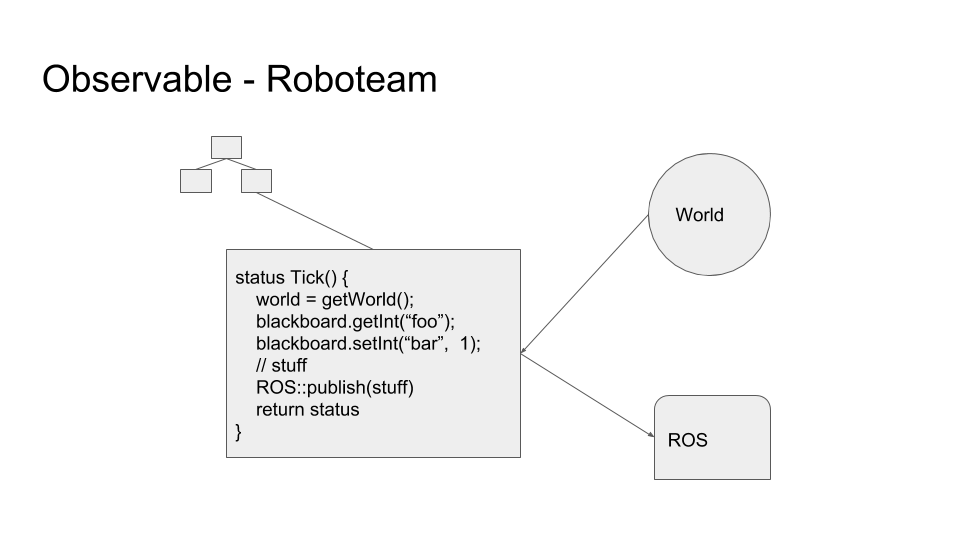

Another related problem was that these leaf nodes, or skills as we call them, are basically untestable because they touch a lot of global mutable state and do a bunch of IO.

I believe these skills became so large and complex because the smaller skills that live inside them have complex interdependencies that cannot be easily expressed in behavior trees. There is not really a good way for these nodes to pass parameters around.

The conventional method for sharing information between skills is using “blackboards”, which are more like “inverse blackboards”, where rather than one person sharing information with the whole room, everyone is running around chalking random stuff all over the board.

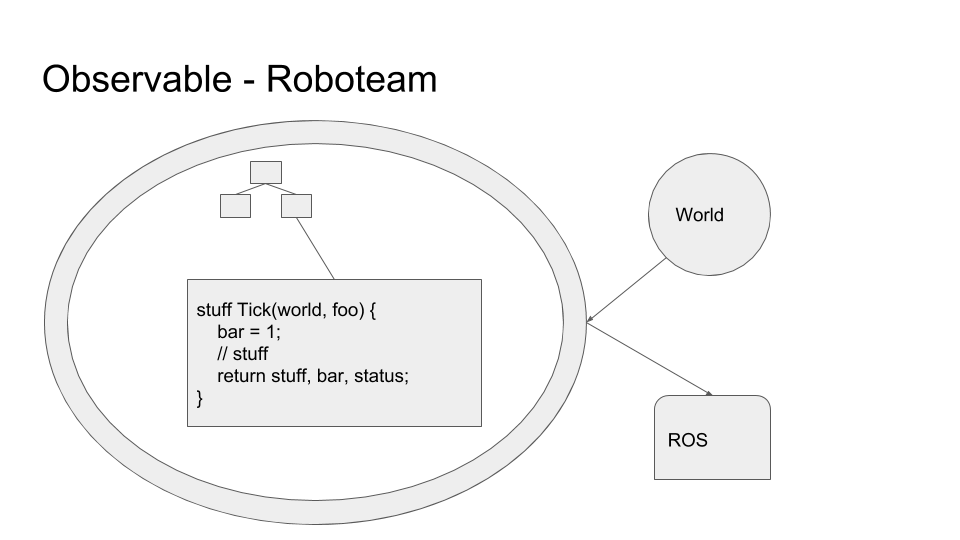

So my first implementation applied some basic functional programming. All our skills look basically the same, get the world state, do some logic, and send messages. So I simply made all the nodes take the world state and return a list of messages.

However, this seemed way too specific, and did not really solve the problem of passing parameters around between nodes. Once I had generalized the list of messages to a parameter stack, the realization struck me that I was doing concatenative programming! I repeat:

Behavior Trees are Concatenative Programs

The idea that I was basically building a domain-specific stack-based concatenative programming language lead to a boatload of new ideas and implementation methods.

I particularly liked the way Forth has this hybrid between compiling and interpreting that allows very efficient yet very interactive programming. I also took a long, hard look at how Joy formalized statically typed concatenative programming in a purely functional way.

My second implementation was in Clojure, and I was delighted by how short and expressive it is. I will repeat my FizzBuzz implementation as a behavior tree below, where you pass in a number, and it returns a number or a string.

(defn fizzbuzz [n]

(-> {}

(spush n)

(selector

#(sequential %

(modn 15)

(message "FizzBuzz"))

#(sequential %

(modn 3)

(message "Fizz"))

#(sequential %

(modn 5)

(message "Buzz")))

speek))Seeing how the Clojure implementation played out, I doubled down on the concatentative programming language, and started work on an actual compiler for my DSL.

The third implementation is an actual compiler that fulfills most of my Joy aspirations. It compiles a statically typed Forth-like language to C code, where you can easily implement new words in C.

There is no explicit stack or API for defining words. I parse your C headers for compatible functions, and compile your Bobcat code to a series of function calls on regular C stack variables.

There is no conventional control flow in Bobcat. It has quotations (which compile to function pointers), and special forms for function definition and – importantly – interpreting a quotation as a behavior tree node, which adds the necessary control flow to implement all the usual behavior tree nodes (sequential, selector, etc.) as C functions.

One noteworthy feature is that there is actually a separate stack per type. I think this is a good trade-off for a DSL, compared to the homogeneous stack of words seen in most stack-based languages. This limits your ability to have generic words like swap and dup, but allows dealing with many things, without too much stack juggling. Those details are mostly handled in the host language.

A funny detail I implemented is the comma operator, which is like executing words in parallel. Much like Clojure’s juxt.

As a small example, something simple like 2 dupi addi 5 muli will compile to the following (which GCC can basically optimize to *out_0=20)

void test(int *out_0)

{

int var_1 = 2;

int b_1;

int c_1;

dupi(var_i, &b_1, &c_1);

int c_3;

addi(c_1, b_2, &c_3);

int var_2 = 5;

muli(var_2, c_3, &c_e);

*out_0 = c_5;

}With something like dupi simply defined as

void dupi (int const a, int* b, int* c) {

*b = a;

*c = a;

}What is sill missing is a more powerful way to work with quotations, which are at the moment useless and broken outside of function definitions and behavior tree nodes. And a really big omission in this design is interactive programming. I want this quite badly, so maybe some day there will be a fo(u)rth implementation, which will be more like Forth.

But for now, I’ve started my masters and a new job, so I had to put a halt to this development. However, I still think this is a powerful concept that will allow writing more expressive, small, testable behavior trees.