I’ve been thinking about making my own 8-bit retro hand-held console, not unlike a GameBoy Color. 8-bit microcontrollers and buttons are easy to come by, memory, sound and a display not so much.

The Atmega2560 used in the Arduino Mega has support for external memory, which is nice. This allows up to 64kb of RAM, and even more if you implement bank switching.

The display is an unsolved problem for me so far. Sure, there are dozens of display shields and breakouts, but pushing pixels over a serial bus with an AVR is just too slow. If you just make the Arduino sit in a busy loop sending bytes over SPI at top speed, it takes hundreds of milliseconds to update the whole screen.

The proper way to do it seems to be to have a framebuffer that you DMA to the screen controller, while the CPU is busy making the next frame. Except the only chips I found that support DMA can hardly be considered retro, and often not even 8-bit. We’re talking 32-bit, 100Mhz chips like AVR XMega, dsPIC or ARM Cortex-M3 here. While the GameBoy does all of that at 4Mhz. I’m not sure what kind of black magic that is.

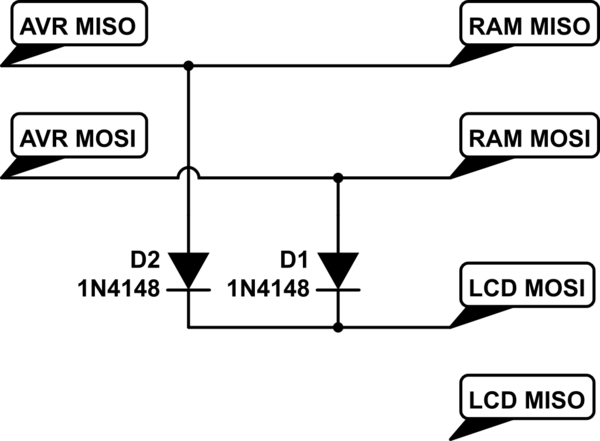

In this moment of despair, I came up with a way to do something like DMA on the Arduino Mega. I figured that with a couple of diodes I could transfer data from a RAM chip to the screen.

Normally you’d connect both the RAM and the screen to the SPI lines and give them a chip-select line each. What I did is disconnect the MISO of the screen and connect the MISO of the RAM to the MOSI of the screen. This way, if you lower both CS lines and send a zero, a byte is transferred from the RAM to the screen.

The hack that makes this work combines code from Adafruit_ILI9341 and Adafruit_FRAM_SPI, which results in the following glorious disaster

void framDMA() {

// set up the display

spi_begin();

tft.setAddrWindow(0, 0, ILI9341_TFTWIDTH-1, ILI9341_TFTHEIGHT-1);

// set up the RAM

digitalWrite(fram._cs, LOW);

fram.SPItransfer(OPCODE_READ);

fram.SPItransfer(0);

fram.SPItransfer(0);

digitalWrite(tft._dc, HIGH);

digitalWrite(tft._cs, LOW);

// at this point BOTH the display and FRAM are active

// Send zero's

for(int i=0; i<ILI9341_TFTWIDTH; i++) {

for(int j=0; j<ILI9341_TFTHEIGHT; j++) {

SPDR = 0;

while(!(SPSR & _BV(SPIF)));

SPDR = 0;

while(!(SPSR & _BV(SPIF)));

}

}

// release the cs lines

digitalWrite(tft._cs, HIGH);

digitalWrite(fram._cs, HIGH);

spi_end();

}I think it’s a nice hack, and if you rewrite the loop as an ISR it could definitely free up CPU cycles. But the actual updating of the screen is still too slow for any sort of annimations.